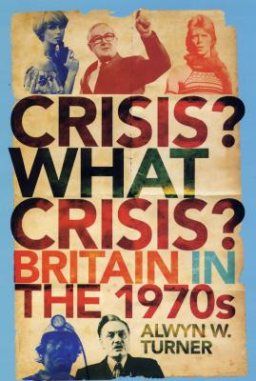

Alwyn W. Turner

London: Arum, 2008, h/b, £20

Punk monetarism

The 15 years from 1969 to 1984 convulsed British society and pulverised its economy. By the end of this period, the post-war settlement, which had been assumed to last more or less indefinitely, was in ruins and the economic and social order we inhabit today was beginning to take shape.

Now, of course, that order is falling apart, as the full consequences of what has been called ‘turbocharged capitalism’ have become apparent. With history moving so rapidly, the day before yesterday recedes in the rear-view mirror. Sooner than we think, writers will be trying to assess the legacy and meaning of the 20 years from the mid-Eighties to the credit crunch, the era of market triumphalism and the victory of high finance. Which, in turn, means anyone wishing to write about the period immediately prior to that era had better get their skates on.

Fortunately, Mr Turner has done so. The press release for this excellent book rather unfortunately declares that it ‘taps into the current fascination with the 1970s and celebrates the era of camel hair coats, David Bowie and Mk2 Ford Cortinas popularised by Life on Mars.’ Some of us cannot get too little of the ‘current fascination with the 1970s’ and it is greatly to the author’s credit that his book is entirely free of sniggering references to tank-tops, loon pants, dreadful haircuts, purple curtains and other Abigail’s Party-type stage props. True, much of the perspective is from that of popular culture, but the first thing this book gets right is to take seriously the decade in question as a time of crisis and upheaval. Even the now-derided fashions seem to be treated with respect – the turned back cuffs, flares and foulards may seem amusing now, but at the time were thought of as denoting a soigné elegance.

The second piece of good judgement follows from the first: this book is the fruit of an extraordinary amount of research. The author has eschewed the dashed-off, the impressionistic and the solipsistic, although his own perspective on the Fright Decade would have been as interesting as anyone else’s, his adolescence having been shared between a British forces base in Germany (his father was a senior Army musician) and a boarding school in the English countryside (your reviewer was a fellow pupil). Instead, archives have been ransacked and key figures interviewed, from Tony Benn to Zandra Rhodes. The author has done his homework and his fieldwork, but it is good to report that neither is allowed to clutter the narrative.

But what is that narrative? In one sense, it is a familiar one.

‘As the amphetamine rush of the ‘60s wore off, the country was confronted by a series of crises that set the tone for the remainder of the century and beyond: crises about natural resources, about race and immigration, about terrorism and environmental abuse, about Britain’s position within Europe and that of nationalism within Britain, crises in fact about everything from street violence to class war and even to paedophile porn. It was a time when the certainties of the post-war political consensus were destroyed and it was unclear what would emerge to replace them.’

The notion that our own social, economic, political and cultural conditions are directly descended from the upheavals of the 1970s is not unique, although it remains surprisingly rarely-held, most people still preferring lazy references to the ‘bad old days’ of that decade in contrast to the supposed abundance and dynamism of today.

The most obvious parallel work to this one is From Anger to Apathy¸ by Mark Garnett (Jonathan Cape, 2007). The differences between them are not confined to the fact that Garnett’s book, another rattling good read, traces the story from the mid-1970s to now, while Mr Turner begins in 1970 and calls a halt when Mrs Thatcher takes office in May 1979. Mr Garnett is unafraid to interpose his opinions into his own narrative, as when he declares that private medicine and education should have no place ‘in a democratic society which wanted to see itself as genuinely fair and meritocratic’. You get the feeling that Mr Turner would consider this sort of intervention to be rather bad form. Like the airline pilots, he disturbs the journey only occasionally, usually with a wry aside, as when he notes that:

‘1977 was supposed to be the year of punk, and certainly the music industry believed it to be so, dropping entire rosters of semi-established acts and signing every guitar group who had the foresight to get a short haircut on the way to the Oxfam shop for a second-hand suit.’

As our own economic order starts to crumble, never forget how bad things can get. It is sobering to remember that penalties for breaching Government regulations on electricity use during the 1972 miners’ strike were three months in prison or a £1,000 fine in today’s money.

The author does not duck any of this, nor the frightening levels of violence, from ‘queer’ and ‘Paki’ bashing to Northern Ireland. While pressing the notion that music, film and television in particular were enjoying something of a golden age, he reminds us of such awkward facts as the chart-topping status of Don’t Give Up on Us – a treacly ballad by David (Starsky & Hutch) Soul – at a time when David Bowie’s majestic Heroes could not make the top 20.

We are spared the comforting idea that at least we all started eating curry and Chinese food, thus laying the foundations for today’s much-vaunted (and much-overstated) ‘tolerance of diversity’. The author prefers to notice that trade unionists were almost entirely absent from television drama – non-persons on the small screen. And his style is almost old-fashioned in its fluency and its avoidance of contemporary horrors. For example, give or take the odd isolated outbreak, the modern misuse of the word ‘gender’ is avoided.

One major regret is that Mr Turner chose to bring the curtain down in May 1979, given that the remainder of that year saw the changes of the 1970s start to crystallise. The Tories’ first Budget switched the burden from direct to indirect taxation, hitting poorer families harder than wealthier ones. The war in Northern Ireland claimed Airey Neave, Lord Mountbatten and 18 British soldiers. Technology, touted in the 1950s and 1960s as the key to a glittering future, had become a threat, as newspapers and the airwaves filled with doom-laden talk of the millions of jobs about to be destroyed by what was then called the ‘silicon chip’. And Alec Guinness kept the nation spellbound with the television version of John le Carré’s 1974 novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. It depicted the tempting of senior UK espionage moguls with a one-off, spectacular solution to Secret Britain’s ills, a Soviet super-spy who would get us back in with the Americans and restore our standing in the world. In the real world, this sort of search for a painless way to get the Great back into Britain had been the biggest casualty of the 1970s.

Now came the 1980s, and the painful way. We can only look forward to Mr Turner’s treatment of what came next.