Andrew Emmerson and Tony Beard.

London: Capital Transport, 2004, £25.00, h/b

Gimme Shelter(s)!

The secret underground government structures that originated during the Second World War and were later adapted, enlarged and augmented for the Nuclear Age were given a once-over by Peter Laurie in Beneath the City Streets (1970) and given much more detailed treatment in Duncan Campbell’s War Plan UK (1982), but with the publication of Emmerson and Beard’s study we have what I guess is the definitive study of the subject, certainly as far as London is concerned. It’s hard to think what more could be written about the period in question (1930s to 1960s).

Some twenty chapters take us from the first ‘alternative’ use of the tube tunnels during the First World War, the deep-level shelters that followed some twenty years later during the Second World War and their subsequent adaptation and modification in the post-war Nuclear Age, and ending with their abandonment and, sometimes, selloff to the private sector for archive storage and other uses.

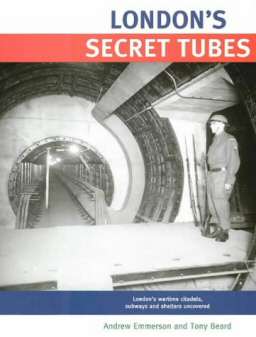

There’s a wealth of photographs here, more than one could have imagined, and these are well complemented by a detailed text that sometimes loses sight of the big picture but makes up for it (?) by telling you exactly where the spoil from the deep level tube shelters south of the Thames was dumped (Clapham Common, Nightingale Lane, and the grounds of a convent).

There’s one small but important point that needs correction. In their preface the authors acknowledge the work of previous writers on the subject and say that Peter Laurie ‘with his book Beneath the City Streets set in motion a zeal for delving deep to expose subterranean secrets.’ Well, that’s about as wrong as you can get. Laurie’s book, as noted above, was published in 1970. The zeal started seven years earlier with the Spies for Peace handing out a pamphlet, Danger:Official Secret, in April 1963 on the Aldermaston March. This lifted the lid on the Regional Seats of Government and other clandestine installations and set me and several of my friends spending much of our spare time searching out bunkers and other underground structures. And we were not alone: many others were doing it too (but we were reporting back to Nicholas Walter, one of the original Spies for Peace, though he never admitted it to us). Nowhere do Emmerson and Beard mention Spies for Peace though they would have seen references to them in Laurie’s book. An odd oversight.

This belongs on the shelf next to English Heritage’s Cold War: Building for Nuclear Confrontation 1946-1989 (reviewed in Lobster 46) that looks at the subject nationwide.