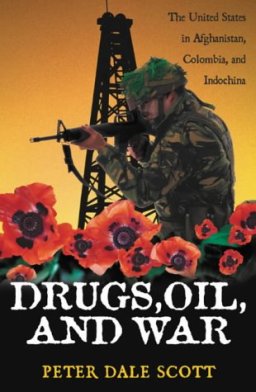

Drugs, oil and war

Peter Dale Scott

Oxford (UK) and New York : Rowman and Littlefield Inc; 2003, $22.95, p/b

On the left-hand page facing his first page of text Scott gives us two definitions of deep politics, the concept he introduced which succeeded his earlier concept of parapolitics.

deep politics: ‘all those political practices and arrangements, deliberate or not, which are usually repressed rather than acknowledged.’

deep politics: ‘the immersion of public political life in an immobilising substratum of unspeakable scandal and bad faith.’

This book is a deep political analysis of some of America’s post-war foreign policy.

If you have read Scott, you need read no further: a new book by Scott is an occasion. If you haven’t read Scott, the only way to convey what he does is to use quotes. Here’s a section from p. 4. This is Scott laying out one of the theses of the book.

‘An under reported factor in the political corruption of U.S. Asian policy has been the input of money, including drug money, from foreign governments through their lobbyists and PR firms. This book will talk about cash injected into the U. S. political system by the China lobby, allegedly drug financed, to back pro-KMT politicians like the young Richard Nixon.10 As the China lobby waned in the 1960s its place was taken by the Korea lobby, with Anna Chennault, the general’s [Claire Chennault], young Chinese wife, playing an important role in both.11 To this day the money from Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church, an offspring of the KCIA and the related Asian People’s Anti-Communist League (APACL, later the World Anti-Communist League or WACL), continues to subsidise the right-wing Washington Times.12

Two deeper factors reinforce the continuity sketched in the preceding paragraph. One is the continuing involvement of regular or “rogue” CIA officers , such as Ray Cline or Edwin Wilson, at every stage.13 Another, not unrelated, is the recurring allegations that the China Lobby, the Unification Church and the APACL have all derived their considerable budgets from the drug traffic.14 At the origins of this insidious influence one finds the undoubted drug involvement of the CIA’s airline CAT (later Air America).15

This is dense, documented, presumes a deal of knowledge on behalf of the reader and touches on what normally passes for the subject ‘American foreign policy’ not at all. It is also very simply and clearly written.

Here’s another section two pages later.

‘This apparent digression into trails leading from covert operations to political influence, and ultimately to drug airlines and mob-controlled banks, is the story that I first explored in The War Conspiracy and again (with respect to the Contras) in Cocaine Politics….essentially the same lobbies and their milieus, with oil prominent at the overt level and mob and drug links at the deeper covert level, play recurring roles.’

Twenty pages later he gives us the book’s major theme:

‘In the half century since the Korean War the United States has been involved in four major wars in the Third World: in Vietnam (1961–75), in the Persian Gulf (1990–91), in Colombia (1991–present), and in Afghanistan (2001–2002). All four wars were fought in or near significant oil-producing areas. All four involved reliance on proxies who were also major drug traffickers.’

Here is another way of looking at it. Because it remains the official stance of the US state, and its self-image, to a large extent, that the US is not an imperial power,(1) its actual imperial policies have to be carried out as far as possible in secret; certainly far away from the gaze of the American electorate and their politicians. In so doing the US has mostly sided with the rich, the powerful, the authoritarian, the criminal and the corrupt – those trying to extend or merely hang onto their wealth and/or influence using American power. This combination of secrecy, deception and scumbag allies, creates deep politics, the ‘immobilising substratum of unspeakable scandal and bad faith’ in which the US’s foreign policy – its undeclared foreign policy – has been intertwined with the global drug traffic.

The book consists of new essays by Scott centred on recent US activities in Colombia and Afghanistan (oil companies and drug traffic allies, again) and the reprinting of some chapters, with commentaries, from Scott’s 1970 book The War Conspiracy on Vietnam (oil and drugs there, too).

There are criticisms of Scott’s methods which could be made of anyone doing contemporary history. Some of his sources are newspaper reports – mere journalism to academic historians – and what is going on cannot always be seen for sure. In an 11 line paragraph on p. 47, for example,’are said to’ appears twice and ‘has been alleged’ once. But this is unavoidable; and Scott doesn’t try to conceal it. In trying to put together, from a series of tiny clues, a picture of events which were intended to be secret, some things will be uncertain and some things will be wrong. But he uses so many sources that even if some prove to be false, the overall picture is not badly damaged. If this is unsatisfactory to the purist historians, it is also the best we can do. There is no point in sitting waiting for the official files to be opened: this material simply won’t be in them.

Notes

1 In October President George Bush said to a joint session of the Congress of the Philippines: ‘America is proud of its part in the great story of the Filipino people. Together our soldiers liberated the Philippines from colonial rule.’ < http://tinyurl.com/s57w >

Bush probably simply doesn’t know that in so doing US forces killed approximately 200,000 Philipinos.