Philip Hoare,

Duckworth Press, London, 1997, £16.99

The opening of MI5’s archives up to and including 1919 gives historians and researchers the chance to exhume the genesis of the right in British domestic politics as well as the early activities of the secret state.

Despite its title (Oscar died in 1900) Hoare dips quite a big toe into this area, examining the career of Noel Pemberton-Billing (1881-1948). Substantial original research has been carried out to bolster the key finding in the text: Pemberton-Billing was used in 1917/18 by the security services and the ultra-right (of which he was a keen member) to smear and damage a number of mainstream politicians, mainly the Asquith Liberals, who were seen to threaten the emerging Lloyd George corporate/military state.

Hoare sketches the background against which this unfolded. Theatrical, social and sexual mores are analysed, as are both the enemy spy hysteria of 1915 and the belief of the time in a unique German /Jewish form of decadence (cue Krafft-Ebing and Freud). The grind of a nation fighting a protracted modern war (death, bereavement, rationing and epidemics) is detailed. The connection this has with the politics of the time is slightly unclear, but it is, of course, the same cocktail that ultimately produced the NSDAP in Germany and Mussolini in Italy.

Pemberton-Billing was not the first demagogue to appear in British politics. After an early outing in Mosley’s later stamping ground of Mile End, in early 1916 he entered the House of Commons via a bye-election at Hertford, in March that year. He took his seat as an ‘Independent’ and was released from his war duties in the Royal Naval Air Service. He soon struck up a working relationship with Henry Page Croft, a tariff reform/anti-Indian self-government Tory MP. Soon afterwards Page Croft was appointed Deputy Lieutenant of Hertford (was this a coincidence?), split from Lloyd George’s coalition and launched the National Party. Their HQ was at 22 King Street SW1, next door but one to the home of Horatio Bottomley – a classic fellow traveller of the right and another populist demagogue.

Pemberton-Billing and Page Croft did not waste time. The National Party were much taken with the (supposed) link between established British Jews and the larger German immigrant community. They advocated Jewish ghettos, the wearing of yellow star badges (‘by aliens’) and campaigned against ‘corruption’. In June 1917, at a National Party meeting, Pemberton-Billing met Henry Hamilton Beamish. Beamish said the country was secretly run by a ‘Jewalition’. Pemberton-Billing and Beamish launched, with funding from Lord Beaverbrook, the Vigilante Society – complete with its own newspaper, The Imperialist. Initially this might have looked (to Beaverbrook) like a good, oppositionist, maverick wheeze but after sampling the ranting of Arnold White –

‘….Germany has found that diseased women cause more casualties than bullets. Controlled by their Jew-agents, Germany maintains in Britain a self-supporting, even profit-making army of prostitutes….’

and the paranoia of Pemberton-Billing, who maintained that 47,000 people in public life had been corrupted by German decadence – Beaverbrook pulled the plug. From February 1918 funding came instead from The Morning Post, later to be the enthusiastic publicists of The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion.

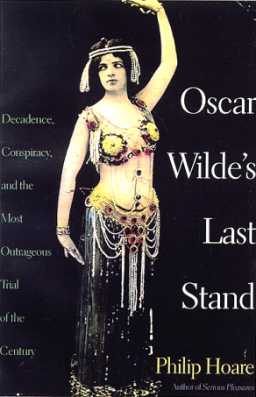

This brought into action the final player in the Pemberton-Billing/Page Croft/Beamish team Lt. Col. Charles A’Court Repington (‘….career ended due to an indiscretion, 1902…’ according to the Dictionary of National Biography), the military correspondent of the Morning Post. Repington fed smears, gossip and intelligence to Pemberton-Billing. There were still some desultory peace talks with Germany under way. Repington (and those who backed him) wanted these stopped. Many allegations were aimed at Asquith and his supporters. A friend of the Asquiths (Maud Allen) was appearing, as a dancer, in a production of Wilde’s Salome. Pemberton-Billing said she was a German agent corrupting British morals and sapping the nation’s ability to see the war through to a grim conclusion. Allen was an easy target, she had once modelled a sex manual for women. She rose to the bait and sued.

Hoare describes the trial, which lasted for 7 days in May and June 1918, with great thoroughness. It coincided with the final Ludendorff offensive in the west – something Pemberton-Billing exploited to relentless effect. The reputations of those in political life whom the military had found wanting were systematically blackened. The tool to achieve this was one Captain Spencer (ex-Admiralty Intelligence, retired on mental health grounds, utterances therefore deniable) who passed information from Repington to Pemberton-Billing. It was all faithfully reported in The Morning Post.

But although the trial ended with the acquittal of Pemberton-Billing he was soon discarded by the right. The failure of the German offensive and the realisation that the war might, after all, last only a few more months meant that he simply wasn’t needed. The establishment scented victory without him. Attempts by the Vigilante Society to get Beamish (Clapham, June 1918) and Spencer (East Finsbury, July 1918) elected in parliamentary bye-elections both failed. Soon after this Pemberton-Billing and Bottomley set up the Silver Badge Party to milk the votes of ex-servicemen. Again, they were outwitted. Although the Silver Badge Party and the National Federation of Discharged and Demobilised Soldiers and Sailors sponsored 31 candidates in the 1918 general election – and 2 of these got elected – the British state moved rapidly to take over leadership of the ex-serviceman movement. By May 1921 the Royal British Legion was up and running. There would be no British Mussolini and no British Hitler. Beamish (a candidate for the latter) founded the Britons Society and moved to Rhodesia.

This coincided with Pemberton-Billings’ exit from national politics. Although he lived until 1948 he resigned in May 1921, citing ill health. Horatio Bottomley (now fronting the Independent Parliamentary Group, and working closely with Lord Rothermere’s Anti-Waste League) slotted in Rear Admiral Sueter to replace him. It all sounds carefully prepared and the simple explanation for Pemberton-Billing’s odd career is that he was someone the establishment were happy to use, and who, in turn, was happy to do them favours.

Some extra research might have yielded dividends. Rene MacColl’s rather old biography Roger Casement, originally dating from 1956 but much reissued since, is a good point for cross referencing. Pemberton-Billing was in action as early as April 1916 (just a couple of weeks after his election) demanding that Casement be shot out of hand. The leaking of Casement’s captured diaries – describing homosexual activities – was deliberately timed to occur between his conviction and his appeal. MacColl points the finger at either Captain Hall (Naval Intelligence…. yet another nautical connection) or one G. H. Mair, a leader writer for the Manchester Guardian, the great Liberal newspaper. Casement’s appeal was heard – and dismissed – by the same judge who dealt with the Pemberton-Billing/Allen trial, Mr Justice Darling, an ex-Conservative MP.

Other parallels? Both Wilde and Casement were Irish, both were gay, both were Protestants. How the English establishment takes its revenge! (And how little good it did Asquith and his crew trying to play along with these elements.)(1)

This is beyond the scope of Hoare’s book. Despite this he sheds much light on the genesis of the ultra-right in British politics. The mechanics of how the National Party was launched, its objectives, the role of the Admiralty as a recruiting ground (Pemberton-Billing, Beamish, Spencer, Sueter) are all fresh contributions to our knowledge of the period. But a work setting out the tributaries that connect, say, the National League for Clean Government with Pemberton-Billing, Page Croft and Beamish through to Mosley, the National Front and the BNP has yet to be written. Perhaps a full account isn’t possible – after all these people don’t exactly leave minutes of their meetings for posterity.

Note

- Captain ‘Blinker’ Hall later sat as a Conservative MP 1918/1924 and 1925/ 1929; he was Conservative National Agent 1923/1924 during the furore over the fake Zinoviev Letter; and one of the founders of the Economic League.